Managing Climate Change Risk on the Bleeding Edge

We pay insurance companies to manage our risk. For a monthly fee they take over the financial risk of disasters. So, if we have fire, rather than having to pay the entire cost of repairs and replacement, we only pay our deductible plus our monthly fees and insurance takes care of the rest. Managing risk is the core business of insurance companies, so it should come as no surprise that they are expending considerable time and effort on understanding the financial risks caused by climate change—and how to manage them.

Dr Janis Sarra, a Professor of Law at UBC, recently wrote a paper for the Canada Climate Law Initiative that employs the same framework Governance for Our Kids Climate uses, albeit on a much larger scale, to guide insurance company boards through the myriad issues wrapped up in climate change.

Sarra points out there are risks on both side of insurers’ balance sheets: “On the liabilities side, more frequent and severe wildfires, flooding and other acute and chronic events are increasing claims volumes while the probabilities of occurrence are becoming harder to predict and price.” On the assets side, she notes: “Climate change impacts all insurers in terms of their management of assets and the financial risks associated with carbon-intensive investment portfolios.”

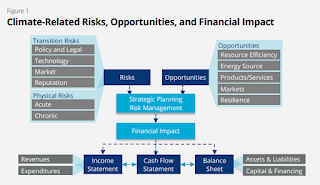

Sarra proceeds to examine the risks to property and non-life insurers, then to life insurers. For each, she uses the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework, looking at physical risks and transitions risks, including regulatory, market, technology, litigation, reputational and social risks. Sarra also provides a section on effective climate governance, again based on the TCFD framework, that looks at governance structure, risk management practices strategy, targets and metrics.

Some interesting observations in the paper:

- The Bank of Canada observes that climate change “looms as a potentially large structural change affecting the economy and the financial system”. This results from climate change causing, ”unexpected re-evaluation of assets in debt and equity securities held by insurers and increased probability of default due to pressures to devalue assets”

- “Canadian securities regulators have stated that climate change is now a mainstream business issue, and publicly-listed insurers and other companies must disclose material climate risks and how they are managing them,” and “boilerplate disclosure is no longer acceptable.”

- “anthropogenic (human-caused) climate change is the biggest long-term risk for insurers, posing a “very large, even existential, threat to the insurance industry”

- “insurers’ concerns no longer comprise only particular acute events; rather, they are the interactions between the global climate and human systems, finding that “because its effects are systemic, climate risk is likely to stress local economies and —more grimly— cause market failures that affect both consumers and insurers.””

- “Adaptation measures may prevent or reduce risks, but the location of businesses, homes, and commercial properties may render them uninsurable. In California, insurers have refused to cover more than 340,000 homes because of the extreme risk of wildfires.”

- “changing market preferences are not limited to the oil and gas sector; they include other carbon-intensive sectors such as transportation, real estate, electricity generation, heavy industry, and agriculture.”

Sarra points out another concept that few of us think about: “Insurers perform a critical function for society by putting a price on risk, and in some cases, constraining capacity, which can help guide behaviour, for instance, decisions regarding whether or not to build on a flood plain. These price/availability signals may help governments and society identify where risky behaviour should simply cease or where adaptation and mitigation actions are required.”

Sarra’s paper is targeted at an extremely large, complicated, complex industry and is beyond what smaller, less financially intense sectors need. However, it does validate the TCFD framework as a tool for boards, regardless of their sector or complexity. It also illustrates the scary magnitude and severity of climate change in the oh-so-dry language of financial risk.

Comments

Post a Comment