Ottawa’s next push on ‘green homes’ is to require an energy audit before you can sell

Ottawa’s next push on ‘green homes’ is to require an energy audit before you can sell

KATHRYN BLAZE BAUM ENVIRONMENT REPORTER

Ottawa’s next push on “green homes” is to require

energy-efficiency ratings for houses going on the market – a controversial

approach that sits at the nexus of hot-button issues in the country: climate

change and real estate.

Officials in the Department of Natural Resources are working

on a proposal for mandatory energy-performance audits of residential homes

before the point of sale. This would require the buy-in of the provinces and

territories, which have jurisdiction over the sale and development of real

estate.

If such initiatives in other countries are any indication,

homeowners would have to post their property’s energy-efficiency rating on

their listing. International research shows that higher energy-performance

scores are correlated with increased property values.

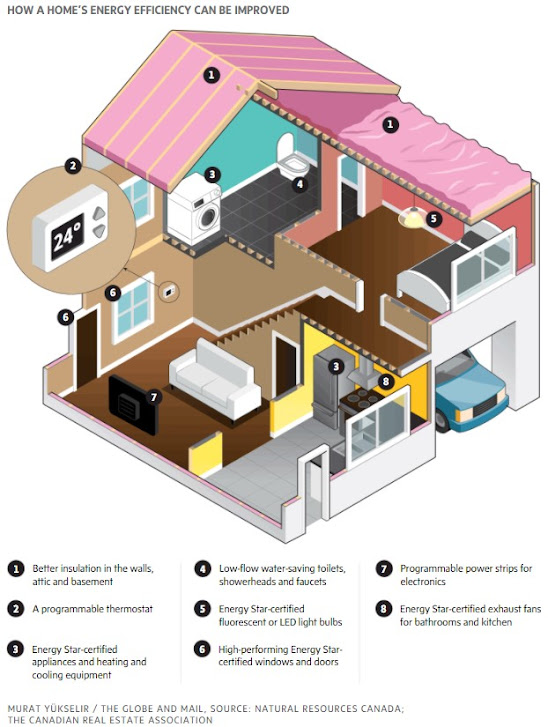

Time-of-sale labelling is part of the federal government’s

blueprint to achieve net-zero emissions from buildings by 2050. It’s

effectively the policy companion to the Canada Greener Homes Grant program,

which helps homeowners cover the costs of investments in energy-conserving

improvements such as electric heat pumps and better attic insulation.

The Liberals have had energy-performance labelling on their

radar for years, and the party highlighted it as a platform commitment during

last fall’s federal election.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has since made clear that compulsory labelling for homes at the time of sale is a priority for his re-elected government. Last month, he updated the Natural Resources ministerial mandate letter to include mandatory efficiency labelling under the federal EnerGuide ratings system.

In an interview with The Globe and Mail, Natural Resources

Minister Jonathan Wilkinson said Canada must make progress on greening the

buildings sector, which accounts for 13 per cent of the country’s

greenhouse-gas emissions. Given that approximately 70 per cent of current

building stock will still exist in 2050, compulsory labelling, Mr. Wilkinson

said, should apply to both new and existing homes.

“It will help buyers in terms of understanding the energy

costs they’re going to pay,” he said. “It will help increase the literacy

around energy and energy usage. It also creates an incentive for homeowners to

improve their energy efficiency if, in fact, they want to sell.”

Some form of mandatory energy-efficiency labelling has been

commonplace across much of Europe for more than a decade. Several U.S. cities

have a version of a residential rating program, as does a territory in Australia.

But the prospect of adding another step to the sale process here in Canada is

eliciting opposition from within the real estate industry, especially amid the

country’s tight housing market.

“Mandating labelling at the time of sale is, quite frankly,

a crazy thing to do in the middle of a historic housing-affordability crisis,”

said Michael Thornton, the vice-president of public affairs and communications

for the Ontario Real Estate Association (OREA).

“We have historic lows in inventory listings on the market currently. Another piece of red tape on a home seller will depress listings even more, making it even more costly to go find a home.”

“Of the 27 studies we looked at, the vast majority reported

there was a statistically significant price premium associated with energy

efficiency,” he said. The price premium was typically in the order of 5 to 10

per cent.

Certain provinces and territories in Canada will inevitably

be more supportive of time-of-sale labelling than others. In B.C., several

municipalities have already experimented with voluntary labelling programs, in

co-operation with B.C. Hydro and the provincial energy ministry.

The idea is also referenced in the B.C. Finance Minister’s

mandate letter, which refers to requiring realtors to “provide

energy-efficiency information on listed homes to incent energy-saving upgrades

and let purchasers know what energy bills they will face.”

In Ontario, however, there are bound to be hurdles. Under

the 2009 Green Energy Act, a provincial Liberal government had planned to

require time-of-sale energy audits, but the idea never got off the ground.

While the Ontario Home Builders’ Association (OHBA) welcomed

mandatory labelling, the real estate association mounted a campaign to stop it,

saying the requirements would complicate the sale process and punish low-income

families who can’t afford retrofits. Realtors were also concerned that the

quality and findings of the audits could vary wildly from one adviser to the

next.

Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government

repealed the Green Energy Act in 2019, and the proposed Home Energy Rating

& Disclosure initiative died with it.

A

new home is built in a housing development in Ottawa on July 14, 2020.

SEAN

KILPATRICK/THE CANADIAN PRESS

Brendan Haley, director of policy research for think tank Efficiency Canada, said although movement toward mandatory labelling “really stalled for a while,” momentum is now growing. “It’s just an obvious thing to do, given that we have to retrofit basically all of our buildings by 2050, if not before,” he said.

Canadian jurisdictions contemplating mandatory labelling

initiatives have many models to look to for inspiration, particularly in

Europe. Since 2009, European Union member states have been required to comply

with a 2002 directive that says countries must introduce energy-performance

certificates for buildings that are newly constructed, sold or rented.

Most member states started by issuing certificates for new

residential buildings, and then at a later stage, extended the requirement to

existing homes and, in some cases, public and commercial buildings. The

European Commission is now proposing to go a step further by triggering

mandatory renovations of existing buildings if minimum energy-performance

standards aren’t met.

OHBA president Bob Schickedanz said the association is still

supportive of energy-efficiency labelling for homes going on the market. Houses

built today, he said, use about half the energy of those constructed roughly 30

years ago. He said the EnerGuide audits would be especially useful after a sale,

since the buyer would receive a menu of potential upgrades that would reduce

energy use and costs.

The Canadian Real Estate Association said it will be in

touch with federal officials “in the coming weeks” about the prospect of

mandatory time-of-sale labelling. In an e-mail, spokesperson Pierre Leduc said

the association supports efforts to improve energy efficiency, but not at the

cost of a reduced housing supply.

“Canada is facing a historic supply shortage, and the

government will need to manage the twin goals of vastly increasing housing

supply while working toward meeting climate-change commitments,” he said.

In addition to jurisdictional issues and concerns over

housing inventory, mandatory labelling would require a massive recruitment of

energy advisers who could perform the presale audits under the EnerGuide

system.

Already, homeowners are frustrated by a shortage of

certified advisers, as demonstrated by problems with the rollout of the Greener

Homes program. The initiative provides homeowners with as much as $5,600 for

upgrades and the requisite pre- and post-retrofit EnerGuide evaluations. Some

homeowners have been told it could be months or even years before an energy

adviser would be available.

Mr. Wilkinson said the government didn’t foresee how popular

the Greener Homes program would be (within three days of its launch, more than

32,000 applications were submitted). “Had we known that,” he said, “perhaps we

would have made sure we had put additional resources in place before the

launch.”

Two weeks before the program opened, the government

announced that it would invest $10-million to recruit and train an additional

2,000 federally certified energy advisers. At present, the majority of the

existing 1,250 advisers are located in Ontario, Quebec and B.C. In several

provinces and territories, there are fewer than 15 serving the entire

jurisdiction.

The Canadian Association of Consulting Energy Advisors said

it is confident that the energy-auditing industry could meet the demand

associated with mandatory time-of-sale labelling if given the time to do so.

“The industry is at a place where it can be done,” said

Andrew Oding, vice-president of the association’s board of directors. “The

profession is exploding.”

Comments

Post a Comment