The Canadian oil and gas companies that want to put the brakes on climate financial transparency

Without more transparency, regulators warn Canada's economy will balloon into a 'climate bubble' that may suddenly burst, causing severe economic disruptions — not dissimilar to recent Russian divestment. But companies such as Suncor and TC Energy want to delay some new mandatory reporting rules, according to an investigation by The Narwhal

By Carl

Meyer

March 23, 2022 18 min. read

While some economists warn Canada's economy is ballooning

into a climate bubble that may burst and provoke severe disruptions, dozens of

Canadian companies are pushing regulators of capital markets to delay new

climate transparency rules.

Mark Little wrapped up oilsands giant Suncor Energy’s

February 2022 earnings call by reassuring investors that shareholders would

have more cash in their pockets than the year before.

“We think we have a great company,” Little, Suncor’s CEO,

said on the Feb. 3 call,

which lasted about 40 minutes. “I’m strengthening the balance sheet [and]

making investments for our future to support the continued growth and cash flow

and shareholder returns for many years to come.”

Missing in the conversation that day, however, were any

specific details about how the company’s growth strategy could be thrown off by

the climate crisis, which is causing mass death of

species and stranding millions of people without food or water security, and

will be made worse by fossil

fuel production plans around the world — plans which Suncor, a major

player in Alberta’s oilsands, expects to contribute up to 790,000

barrels of oil equivalent every day.

Little did discuss how his company was focused on driving down carbon pollution from its operations, and Suncor has published information about climate-related risks and opportunities to its business.

But an investigation by The Narwhal has revealed that Suncor

— along with other fossil fuel firms and dozens of companies and organizations

from other sectors — is also pushing back against game-changing financial

disclosure proposals that, if implemented in Canada, would set clear standards

and force companies to be more transparent and specific about how climate

change could disrupt their operations and finances. The Narwhal reviewed the

positions of more than 100 companies and organizations and found the majority

were opposed to such standards.

Canadian regulators released their proposal last

fall, recommending that publicly listed companies should publish climate

disclosure reports with detailed metrics and targets, along with information

about how companies plan to deal with the climate crisis. The proposal was

largely based on recommendations first

made in 2017 by an international committee chaired by billionaire Michael

Bloomberg that calls itself the Task Force on Climate-related Financial

Disclosures.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau speaks with Michael Bloomberg at COP26 in Glasgow on Nov. 1, 2021. Photo: Prime Minister’s Office / Flickr

New rules would mean public companies would need to

regularly publish additional climate information to participate in capital

markets, like the Toronto Stock Exchange, Canada’s largest stock exchange.

As regulators hammer out the fine print of new rules, an

avalanche of Canadian companies and special interest groups — representing a

range of sectors including the oilpatch, mining, manufacturing, utilities,

banking, accounting, investments and insurance — have pushed for a delay to

major reforms.

The pushback is laid out in written

submissions filed over the past several months to the provincial and

territorial regulators of Canada’s capital markets, where companies like Suncor

trade. Regulators of these markets work together to ensure no misconduct takes

place, and coordinate on rules nationwide under the banner of the Canadian

Securities Administrators.

Two-thirds of the companies and organizations that wrote to

regulators between October 2021 and February 2022 said they were opposed to key

measures that would force them to reveal more in their financial disclosure

documents about how they plan to deal with climate-related changes to their

business, according to an analysis by The Narwhal.

Submissions were gathered before the invasion of Ukraine

that has killed and injured thousands of people, upended global markets and led

to a scramble to pull out investments and suspend or shut down businesses with ties to Russia,

including Russian state-owned oil giant Rosneft.

The same scramble is lying in wait for Canadian companies

who cling to polluting assets for too long. The Bank of Canada and the Office

of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions — a federal regulator — also

flagged this threat in January when they released a report showing that if

Canada’s transition to a low-carbon economy is too abrupt or too late in the

game, that could destabilize the economy, send assets

crashing in value and threaten the jobs and retirement savings of

Canadians.

As a result of the looming threat of climate change,

Canadian regulators are trying to intervene in markets before they suffer the

fallout of climate-related shocks. That risk has been behind the push to make

companies much more transparent about the pollution their products are

generating and how their businesses could be disrupted by the climate crisis.

Without that transparency, regulators warn, Canada’s economy

will continue ballooning into a “climate

bubble” that will eventually explode in a disorderly, sudden way — not

dissimilar to how Russian divestment has unfolded.

Tourmaline Oil, Pembina Pipeline lament ‘burden’ of

climate transparency rules

Of all the voices pushing for regulators to delay or abandon

reforms to climate transparency rules, oil and gas companies have been

particularly vocal.

In written submissions reviewed by The Narwhal, company

executives frequently cite the “burden” of the workload that would stem from

having to comply with climate transparency rules.

This comes at a time when oil and gas companies are

announcing billions of dollars in profits in recent earnings reports, with the

sector sitting on about $75 billion in cash. Corporate profits

in Alberta soared

by 147 per cent in 2021, and that was before crude oil prices skyrocketed due

to supply disruptions caused by Russia’s assault on Ukraine.

In February, Suncor announced $1.53

billion in profits, but a month earlier Suncor wrote

a letter to provincial regulators arguing it wouldn’t be “useful” to

publicly reveal one of the proposed transparency exercises, which would have

the company publish what’s known as climate scenario planning.

A view of Wapisiw Lookout in Alberta in June 2010 at a Suncor Energy oilsands operation. Photo: Suncor Energy / Flickr

The premise of climate scenario planning is simple — a

company must explain how it would fare in a world committed to substantially

less carbon pollution. A company might, for example, lay out a scenario in

which the world meets the Paris Agreement goal of holding global average

temperature increases to below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Scenario planning can illustrate both the physical impacts

of climate change and the economic transition ushered in by climate policies.

For example, one scenario, dubbed the “hot house world”

scenario, contemplates how a company’s business will fare if climate policies

fail to slow significant global warming and “critical temperature thresholds

are exceeded leading to severe physical risks and irreversible impacts like

sea-level rise.”

Not one of the oil and gas companies that made submissions

to regulators wrote clearly in favour of immediate mandated disclosure of

climate scenarios. Their submissions also indicate that none of the companies

actually know the full extent of how the climate crisis will damage their

businesses.

For example, while Suncor says it does some internal

analysis of future scenarios and describes this as “beneficial for investors as

it relates to our view of risk,” the company argues it would not “be useful at

this stage” to share this planning with members of the public “because it is

overly complex” and would require making a number of assumptions.

Suncor and others who are pushing back against immediately

implementing tougher rules also argue that because international standards are

still being finalized, any information they do reveal runs the risk of being

inconsistent, especially across different sectors, leading to the potential for

misleading conclusions to be drawn by investors.

Tourmaline Oil, which bills itself as Canada’s largest

natural gas producer, has similar concerns. Tourmaline reported $2

billion in net profits in 2021, but the company complained

to regulators of the “cost” and “burden” to undertake scenario

planning, as well as of another transparency measure that would require the

company to calculate and publish the carbon pollution generated when its

natural gas is burned by consumers. (Suncor also does not support this measure,

citing a lack of guidelines on how emissions would be calculated or reported.)

Baytex Energy, which is active in conventional drilling and

fracking in both Alberta and Texas, also argued the mandatory preparation and

disclosure of the emissions from burning its products “would be particularly

burdensome.”

The company wrote in its submission to

regulators that climate scenario planning “should not be required” to be

publicly revealed because the information used to prepare the exercise is

“inconsistent.” Like Suncor, Baytex too said the results would not be “useful.”

Pembina Pipeline, which operates over 18,000 kilometres of

pipelines carrying crude oil, natural gas and other petroleum products in

Canada and the United States, told regulators in a letter that

while the company recognized the value of climate scenario planning and used

the tool internally, it also believed it should not be required to reveal it to

the public.

There were a number of assumptions required to complete this

exercise, the company wrote, and so it would provide “little benefit to

investors, especially when weighed against the significant costs that would be

incurred by [companies] to prepare such information.”

These oil companies have been backed up by industry lobby

groups. The Canadian Gas Association told

regulators scenario planning requirements should be “excluded in all

cases” because it could lead to “confusing modelling and reporting for

investors and market participants.” The Canadian Association of Petroleum

Producers said in its submission that it was “premature” to mandate scenario

planning as it was “difficult to compare and contrast” scenarios from different

companies.

In response to The Narwhal’s requests for comment, the

Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers said it had nothing further to add

on the topic. Tourmaline Oil, Baytex Energy, Pembina Pipeline and the Canadian

Gas Association did not respond to requests for comment.

How burdensome is climate scenario planning?

Though oil and gas companies repeatedly cite the “burden” of

new scenario planning regulations, whether the effort required is overly

burdensome is a matter of debate.

Bloomberg’s task force produced a “guidance” document in

2020 stating that “getting started using scenario analysis is not difficult.” A

typical process, they wrote, “often takes only a handful of full-time staff and

less than a year (often three to nine months) depending on the size of the

company and the scope of the decisions under consideration.”

The British Columbia Investment Management Corporation, a

large institutional investor in Canada with $199 billion in assets under management,

also argued

in its letter to regulators that “scenario analysis does not need to

be an exhaustive process,” that requires companies to start from scratch. The

corporation wants to see a requirement for scenario planning transparency “for

at least some companies.”

In a Feb. 14 response to The Narwhal’s questions, Suncor

media and social advisor Leithan Slade pointed out that the task force itself

has acknowledged its

guidance document on scenario planning is not meant to be a “checklist of

everything a company should do” to meet transparency standards.

Suncor has “an extensive history of reporting in our annual

report on sustainability and our climate report,” Slade wrote. “Suncor is

committed to credible, transparent and industry-leading sustainability

reporting.”

Slade also said Suncor has prepared a scenario in line with

its support for the task force and Paris Agreement, published

in its climate report, which looked at “a plausible pathway to keep global

temperatures from rising [two degrees Celsius] or less by 2100.”

That scenario analysis is one page long and mostly discusses

the impact on global energy markets. Its section on disruptions to the company

itself is 39 words long and related to growing the firm’s electricity and

hydrogen business, “transforming” the carbon footprint from its oil production

and commercializing unspecified climate “solutions.”

It is difficult, however, to gauge what strategy Suncor is

deploying to address the risks it recognized as part of the exercise, or what

detailed changes Suncor may be considering to its business model — both central

elements to climate scenario planning, according to the task force’s guidance.

Over half of respondents against rules revealing

emissions from their products

Michael Bloomberg and the task force he chairs are not alone

in calling for increased climate transparency in financial disclosures — and

time is of the essence, according to proponents.

Regulators must adopt the task force’s key measures if

Canada has any hope of sticking with its plans to limit pollution and slow

climate change, according to Principles for Responsible Investment, a United

Nations-supported initiative that counts over 4,300 pension funds, insurers,

investment managers and other financial industry entities around the world,

including more than 200 headquartered in Canada. The initiative collectively

represents hundreds of trillions of dollars in assets.

“Nothing less than an ambitious, significant and concerted

whole-of-government approach to regulatory action will be enough to meet the

challenge of Canada’s 2030 and 2050 targets,” the initiative wrote in a letter to

regulators. “This not only applies to decarbonizing Canada’s energy system, but

also leveraging the financial sector to enable and drive deep decarbonization

of the economy.”

Despite this, 84 of the 130

submissions made in response to the regulators’ proposal take issue

with at least one of several key climate transparency measures, The Narwhal has

found.

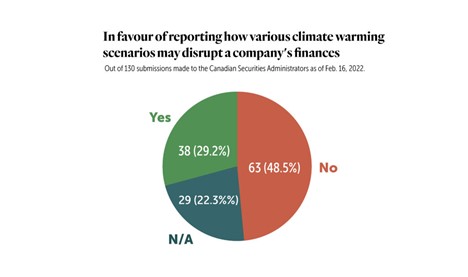

Almost half of the organizations that responded to

regulators were against requiring companies to start disclosing their scenario

planning when the new rules kick in, while under a third were in favour. The

remainder of the respondents either did not discuss scenario planning or The

Narwhal could not determine their position.

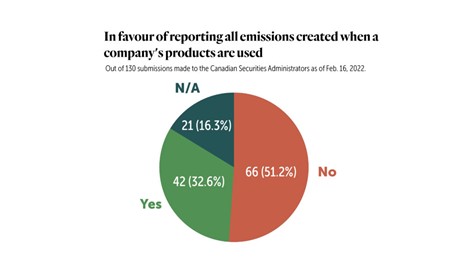

Over half of the respondents said they were against rules

that would make them start revealing emissions from their products, while a

third were in favour and another sixth could not be determined.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission unveils climate

transparency proposal

Meanwhile, the push for more transparency could soon affect

companies trading on American stock exchanges.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) unveiled a proposal on

March 21 that would establish climate-related disclosure requirements, such as

details on how climate-related risks have affected a company’s “strategy,

business model and outlook.”

The U.S. proposal would ask companies to disclose details of

any existing scenario planning already underway. This could include disclosing

any projected financial impacts.

It would also ask a company to publish details of the

emissions from the burning or use of its products if it has set a climate

target that includes these emissions.

“Today, investors increasingly want to understand the climate risks of the companies whose stock they own or might buy,” commission chair Gary Gensler explained in a March 10 video on Twitter, providing an overview of the proposal.

“A lot of companies are already providing such information

about climate risk, but investors representing literally tens of trillions of

dollars are looking for more consistent and comparable information so they can

make informed decisions about where to put their money — and that money is

often the money they are investing for us.”

The European Commission and the United Kingdom are also

pursuing similar regulatory changes.

When the British government carried

out its own public consultations on potential climate-related

financial disclosures in spring 2021, they also asked companies and

organizations about what they thought of rules that would require firms to

publish climate scenario planning.

The British government said it received “mixed feedback” to

this question. Out of 107 responses, respondents were split almost evenly on

whether companies should be forced to reveal this information, with slightly

more in favour of disclosures.

Though the British government was initially reluctant to

mandate climate scenario planning, the survey results and “compelling

feedback” prompted a “reconsideration” of its approach. Scenario planning

requirements will be part of new financial transparency rules that will come

into force in April.

Ernst & Young believes climate scenario planning to

form ‘global baseline’ for standards

Climate scenario planning is also part of a new

suite of financial disclosure measures developed in 2021 that

accounting firm Ernst & Young believes will form the basis of a “global

baseline” for transparency standards this decade, according to its Feb.

15 letter to

Canadian regulators.

The new suite of measures were developed by a coalition

of experts which included Bloomberg’s task force, and

were published in November 2021 — a month after Canadian regulators’ proposal

was published.

Unlike the Canadian proposal, these measures do recommend

that companies publish a “diverse range” of climate-related scenarios — asking

firms to reveal step-by-step details such as the assumptions the company made

as it went about preparing its findings.

In its letter, Ernst & Young urged Canadian regulators

to align their rules with the international standards being developed by the

new International Sustainability Standards Board — including rules related to

climate scenario planning.

“We believe scenario analysis should be required to be

disclosed as it would enhance the competitiveness of Canadian companies

internationally, given certain jurisdictions have already mandated disclosure,”

the firm wrote.

Reforms softened to be ‘sensitive to concerns’ of

companies: Canadian Securities Administrators

The Canadian regulatory proposal itself,

as written in October 2021, excludes certain groups like investment funds from

the new transparency requirements.

The proposal would also not force companies to disclose

their scenario planning, publish the emissions from the products they produce,

or require their emissions to be independently audited.

In the proposal, regulators wrote they deviated from

international recommendations because they were “sensitive to concerns related

to the regulatory burden and additional cost” that companies would bear if

forced to be more transparent.

A number of fossil fuel companies agreed that regulations

should not require them to be transparent about how climate change would

disrupt their businesses

“This approach is appropriate,” wrote Whitecap Resources, a

Calgary-based oil and gas company focused in Western Canada, in a letter to

regulators, referring to their decision not to make climate scenario

disclosure mandatory.

TC Energy made similar comments, writing

in their own letter, “while scenario analysis is useful internal analysis,

we support the exclusion of scenario analysis as required disclosure in the

proposed instrument.”

TC Energy also said they were against requirements to

disclose emissions from the burning of its oil and gas products.

A representative from TC Energy’s media relations declined

to answer questions. Whitecap Resources did not respond to The Narwhal’s

request for comment.

|

| An energy industry worker stands on the doc at the Trans Mountain pipeline terminal in B.C. Photo: Trans Mountain / Handout |

The regulators’ approach surprised Engineers and

Geoscientists BC, the professions’ regulatory body, which wrote in its

own submission that

it was “not clear” why regulators had taken a different path than the

international Bloomberg-led task force.

“The future we are heading into is not well represented by

past data or trends, and in this absence of experiential evidence, scenario

planning is known to be an effective risk management tool,” the group added.

The comment period over the new disclosure rules ended in

February, and regulators now plan to consider all the comments over the next

several months. The proposal suggests a one-year and three-year phase-in

period.

Alberta Securities Commission says some smaller companies

have ‘very real resource constraints’

Tonya Fleming, senior counsel with the Alberta Securities

Commission, has been working with regulators across the country on the proposed

new disclosure rules, and has stressed that the proposal is still being worked

out.

During a Jan. 20 online information session the

commission postedon its YouTube channel, she said it was “very likely” the final version of

the rules “will look a bit different than what we talk about today.”

Fleming said the team has been “meeting with Alberta

companies to talk about what we’re thinking in terms of the proposed rules,”

and listening to their “feedback.”

She said large Alberta companies are “absolutely leading the

way” when it comes to climate-related disclosures “but some of our smaller

[companies] just haven’t started down this path yet.” They may have “very real

resource constraints” preventing them from having the ability to produce the

material, she said.

“We want to respond to the investor needs and align with the

international developments, but we are also cognizant of regulatory burden and

the additional cost that our companies will bear when they respond to these new

climate disclosure rules,” Fleming said. “We listen, we hear from industry and

from investors as to what they’re looking for.”

“We consult with and listen to both investors and issuers

when considering new rules, which is the approach we took on the proposed

climate-related rules,” said Theresa Schroder, senior advisor for

communications at Alberta Securities Commission, when asked for comment on

Fleming’s statements.

The Narwhal asked the Canadian Securities Administrators why

the proposal deviated from the Bloomberg task force’s recommendations, and

which industry associations expressed concerns to them about a “regulatory

burden.”

Pascale Bijoux, senior advisor for communications and

stakeholder relations, said in an email the proposed disclosures are “the

result of engagement and discussion with advisory committees, [Canadian

Securities Administrators] members and a wide range of stakeholders,” noting

the organization also takes approaches from around the world into account.

State of Canada’s climate-related disclosures ‘sorely

inadequate’: finance industry veterans

Climate scenario planning is a crucial exercise meant to

test the resilience of a business strategy, according to the Canadian Institute

of Actuaries, the governing body for the profession that measures risk and

uncertainty. Without it, there’s “no incentive” for companies to start down a

path of increased climate transparency, the group argued in a letter submitted

to Canadian regulators.

The Canadian Climate Law Initiative, a collaboration between

the University of British Columbia and York University, agreed, saying in their

submissions it would be difficult for companies to strategically plan without

using climate scenario analysis. The group has released

a legal opinion concluding “pension fund trustees have obligations to

consider climate change as part of their fiduciary duty.”

The Bank of Canada and the Office of the Superintendent of

Financial Institutions have explained in their own climate scenario planning

why the absence of tougher rules could lead to a disastrous market failure and

massive job losses.

“Meaningful disclosures matter,” Ben Gully, assistant

superintendent for regulation at the Office of the Superintendent of Financial

Institutions, said during

a media briefing on Jan. 14. “Improving disclosures helps financial

system stakeholders respond to clear, comparable and consistent information

about climate-related risks and opportunities.”

Gully made the comments as the Office of the Superintendent

of Financial Institutions — which regulates banks, trust companies, loan

companies, fraternal benefit societies and insurance companies — and the Bank

of Canada released a

report confirming concerns among some analysts who believe Canada’s

climate data from businesses is either incomplete or mediocre.

A joint review

by regulators in six provinces in 2021, for example, found that over

four in 10 companies studied had produced “boilerplate, vague or incomplete”

language on climate risks, while a quarter avoided examining the financial

impact of climate change entirely.

Canadian pension managers view the current state of

climate-related disclosures as “sorely inadequate,” Sara Alvarado, executive

director of the Institute for Sustainable Finance at Queen’s University, chair

Sean Cleary and research director Ryan Riordan, wrote in a letter to

regulators. They pointed to a 2020

statement by Canada’s eight largest pension funds calling for better

financial transparency over environmental factors.

Canadian businesses leaving themselves vulnerable to

‘climate bubble’

Beyond the pressing need for corporations to become more

transparent about their actions and their products so Canadians can see the

planet-warming potential of their businesses, the Canadian Institute of

Actuaries has

also pointed out how this transparency is necessary to connect the

dots between the drivers of climate change and the “volatility” climate change

is causing in insurance claims.

Insurance claims from climate-related disasters have been

substantial. The Insurance Bureau of Canada reported $2.1

billion in insured damage across the country in 2021 connected to

severe weather — the sixth-highest tally since 1983. It represents what the

insurance bureau dubs the “financial costs of a changing climate.” Worldwide,

natural disasters caused overall

losses of US$280 billion in 2021, according to one estimate.

In Canada, last year’s wildfires, droughts, floods and heat domes

hammered home the reality of climate change for many Canadians.

The B.C. government declared a state of emergency on Nov. 17 as severe flooding caused by an atmospheric river cut off all access routes into a number of cities and towns. Photo: B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure / Flickr

Federal scientists warn Canada is warming at more

than twice the global rate, and the risks of flooding, wildfires, heat

waves, rising sea levels and other physical dangers will only increase in the

coming years, affecting Canadians’ health and wellbeing in addition to

influencing practically every economic sector.

But the vacuum of information from Canadian businesses on

how they will weather this coming storm has resulted in a chorus of banks,

financial experts, pension funds and regulators themselves warning the economy

is vulnerable to a ‘“climate

bubble” that, when it bursts, could be financially devastating for families

and communities.

None of that conversation, however, was present on Feb. 3

during Suncor’s earnings call, where executives discussed how diesel demand was

“back to normal,” and how the company’s oilsands assets “contributed record

annual funds” in 2021.

“Suncor is well positioned in 2022 to deliver higher

production,” Little said, adding he anticipated the company’s plans would

“accelerate shareholder returns.”

— With files from Fatima Syed

Comments

Post a Comment